Whilst Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, first announced himself to the world with his breathtaking demolition of the scary Sonny Liston in 1964, landing him the world heavyweight boxing championship at the age of 22, it was perhaps for his encounters in the 1970s against those beasts of the ring Joe Frazier and George Foreman that he is best remembered by many.

Indeed he, and they, dominated the heavyweight scene during the early years of that decade, heralding a golden age of boxing which has seldom if ever been equalled. Even prior to the Liston fight he had declared himself to be “The Greatest” and, both before and after an enforced hiatus brought about by his unwillingness to take up arms during the Vietnam War, he proved himself worthy of the title by going in with, and defeating, the very best.

His intelligent style, picking off his opponents as he strategically retreated around the ring, dancing and shuffling and inviting his dazed and bemused foes to do their worst, made him all but unbeatable in his prime. And with his antics outside of the ring, trash-talking his rivals and predicting (sometimes with the aid of poetry) the timing and nature of their demise, he ensured that he was always a box-office draw.

The early years

Born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1942, the young Cassius Clay took up boxing at the age of twelve with a view to exacting revenge upon a boy who had stolen his bicycle. In the 1960 Rome Olympics he won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division. After turning professional and then converting to Islam, he caused a big upset with his unexpected rout of Liston, who had generally been considered unstoppable. Having abandoned his “slave name” and taking on the moniker by which he would become famously known, he successfully defended his title many times, including against Britain’s own Henry Cooper and a particularly memorable fight against the respected, hard-punching Cleveland Williams.

Then, in 1966, came the draft – and Ali’s refusal thereof. His religious faith, coupled with his distaste for the treatment still being meted out to black people by a country that wanted him to put his life on the line fighting its war, led him to become a conscientious objector. And whilst he managed to avoid imprisonment (he could have been incarcerated for up to five years), he could not get a licence to box and his titles became forfeit. It wasn’t until 1971 that his conviction was overturned on what was in effect a technicality.

Ali in the 1970s – the golden years

Muhammad Ali’s comeback fight took place some 31 months after his previous contest. Any half decent white heavyweight was always good for ticket sales and Jerry Quarry, to be fair, was no mug. He’d defeated Floyd Patterson and Buster Mathis, and had somehow managed to go the distance with Jimmy Ellis with a broken back! Nevertheless the damage he sustained at the hands of Ali led to him being stopped at the end of the third round of their encounter, in spite of his protests. After an admittedly laboured fifteen-round defeat of Argentinian hopeful Oscar Bonavena the stage was set for the big fight against the man whom Ali believed was just looking after his belt – the undefeated “Smokin’” Joe Frazier. But the fight ended with a unanimous decision in Frazier’s favour, and on 8th March 1971 Muhammad Ali had tasted defeat for the first time in his professional career.

More than a dozen fights took place – including another loss, this time to Ken Norton in 1973, avenged later the same year – before Ali would get the opportunity for a re-match against the man he called “the gorilla”, Joe Frazier, at Madison Square Garden. Frazier had recently lost his world title to the big-hitting George Foreman. This time it was Ali who would take the decision after a hard-fought twelve-round battle. This was 1974, and later the same year Ali got his chance to fight Foreman for the world title.

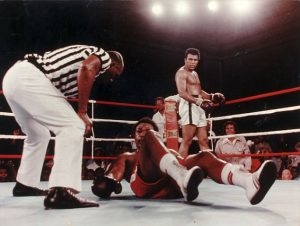

In spite of his past record not many gave Ali much chance against the fearsome power of Big George. With the bookmakers he was a 4-1 underdog. Experts aplenty queued up to deliver themselves of the opinion that Foreman, who had blown away both Frazier and Norton on his way to the title, would just be too strong for him. The fight would take place in the central African republic of Zaire, and became known as “the Rumble in the Jungle”.

The Rumble in the Jungle

But as well as being a sublime pugilist, Ali was known for his intelligence and for his ability to get into the heads of his opponents. He knew only too well that he could not outslug the monster that was George Foreman. He had to fight him his way, rather than allowing Foreman to dictate the fight. As always, Ali had a plan.

Perfecting a technique that he had christened “rope-a-dope”, Ali spent most of the fight with his back to the ropes, covering his face and body as best he could and inviting his adversary to do his worst. Foreman duly obliged, pounding away fruitlessly at thin air and bone for nearly eight gruelling rounds until he had reached a state of near exhaustion. Then, sensing his opportunity against his weary opponent, Ali suddenly sprang to life and despatched the fatigued champion to the canvass. Against all odds, The Greatest was world heavyweight boxing champion once again.

The Thrilla in Manila

Ali took three fights in 1975 before embarking upon the third epic encounter with his eternal rival Frazier. In the first of them, a sloppy but hard as nails journeyman by the name of Chuck Wepner knocked Ali down in the ninth before succumbing in the final round. The UK’s durable Joe Bugner took him all the way, only to lose the contest by a unanimous decision.

Then, in November, came “The Thrilla in Manila”. Ali once again employed his “rope-a-dope” strategy, but many observers felt he had done so out of necessity after he’d tired in the face of Frazier’s sometimes relentless onslaughts. The fight was heading towards an uncertain verdict when Frazier’s trainer Eddie Futch refused to allow his man to come out for the final round, much to the fighter’s chagrin. In truth both is eyes were shut as a result of the punishment that he had taken at the hands of Ali, but the champion too was in a great deal of pain and was said to have seriously considered retirement for the first time in this career.

The year 1976 saw Ali take another second rematch, against Ken Norton, the only other man to have beaten him. Before doing so however he had scored victories over the Belgian Jean-Pierre Coopman, Jimmy Young, and Britain’s Richard Dunn. When he did fight Norton in September 1976 he won by a decision which many observers questioned. It would be almost a year before he would fight again.

A sad and shambolic end to a glorious career

In fact after 1976 Muhammad Ali would fight only six more times. Distance wins over tough Uruguayan Alfredo Evangelista and the frightening Ernie Shavers were creditable enough but in his next bout he lost to Leon Spinks (labelled “The Vampire” by Ali because of his missing front teeth) in what was only the challenger’s eighth professional fight. And although Ali avenged this defeat in a rematch exactly seven months later, he would go on to lose embarrassingly to both Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. When he faced Berbick he was almost forty years of age, and the contest had to take place in Nassau, Bahamas, as no US state would grant Ali a licence. The fight started over two hours late because the key to the venue had been misplaced. It was a sad and shambolic end to a glorious boxing career.

All the same, the illustrious history of Ali the fighter and the legend is one that shines through strongly, quite overpowering any lingering, uncomfortable recollections we may have of his flabby struggles through this final few bouts. The dancing, the shuffling, the poetry, the braggadocio, the shocking self-confidence, the often accurate predictions as to the timing and the methods of his victories, these are what live on when we look back and take stock of the Ali years.

The Greatest

Muhammad Ali was arguably the greatest heavyweight boxer that ever lived, but he was much more than that. Few other boxers have had hit singles written about them, have guested on popular chat shows around the world, and have even found the time to appear in cheesy television commercials in other lands, as Ali did when he went into battle with the Humphreys who were stealing Unigate milk from unsuspecting children in the UK in the 1970s. There were films made about him, and I recall with awe the day when he arrived at London Heathrow’s Terminal Three in the company of Joe Frazier and George Foreman, many years after he’d hung up his gloves, en route to recording a promotional video.

Ali passed away in 2016 at the age of 74, having been admitted to hospital with a respiratory illness just the day before. He had been suffering from Parkinson’s disease from the age of 42, probably as a result of the blows he had taken to the head throughout his time in boxing.

He will be remembered for his extraordinary sporting prowess but equally for his unique personality and charisma, as well as his philanthropy and his dedication to his religious faith. There will never be another quite like him.

If you enjoyed reading this article, make sure you stay updated with all Phil’s latest blog posts by signing up to receive his free Newsletter. You can unsubscribe at any time and your details will never be shared with any third party. Click here to sign up today.